A Game, Life Well Played

Coach Al Buckingham’s career spanned more than 60 years and included stints at Morningside College, with the NAIA and with the Olympics.

By Jody Ewing

September 4, 2003

Al Buckingham is a man who has worn many hats: athletic director, basketball coach, president of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), president of the Olympic’s World University Games, head of state planning — and the list goes on.

For more than 60 years, the die-hard basketball enthusiast immersed himself in every aspect of the game, from competing in the first-ever National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball (NAIB) Championship in 1937 to later serving as the renamed NAIA’s president from 1965 to 1966. He dedicated more than half a century to his venerated alma mater — Morningside College.

Throughout the course of his career he witnessed many changes, which ranged from blacks becoming part of the conference to a women’s half-court, six-on-six game that allowed no contact whatsoever.

As he prepares for the basketball season this fall, Buckingham shares his thoughts and impressions on a game, and a life, that not only has been well lived, but loved.

Setting a Precedence

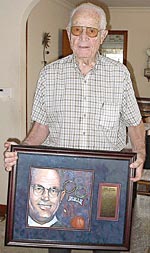

Al Buckingham, shown here in his Morningside, Iowa, home, displays the plaque Morningside College alumni and basketball players presented to him last year honoring his many years of service.

Al Buckingham, shown here in his Morningside, Iowa, home, displays the plaque Morningside College alumni and basketball players presented to him last year honoring his many years of service.

Photo by Jody Ewing

“Basketball used to be a no contact game. Can you believe that now?” Buckingham asks, settling into a chair at his home in Morningside, Iowa. “And we used to coach not to shoot one hand and they do that now. After Hank Lessette from Stanford shot one-handed, about everybody shot one-handed after that. It’s a big change.”

It is two of many changes the coach has seen. The number of referees increased from one, to two, then three. There was a widening of the free-throw circle lane, the game no longer has jump ball and now they use midpoints.

“You used to be able to get ahead of somebody and guard the person who had the ball,” Buckingham says, “but soon they had it where you had to advance the ball. Now they’ve got 45 seconds’ time before they shoot, so it speeds things up a lot.”

Overcoming racial barriers

In addition to changes within the game itself, Buckingham also witnessed the breaking of racial barriers.

From 1945-1947, Rosie Wilson — an African American from Sioux City’s Central High — played with the Morningside team. They’d gone down to Kansas City for the first of three annual tournaments.

“I didn’t have any idea that when we went down to Kansas City they wouldn’t let him sit on the bench,” says Buckingham, head coach at the time. “He had to stay at the YMCA. Then the next year he could sit on the bench but he couldn’t play. The next year he could play.”

In a sense, Buckingham says, Morningside set the precedence to allow blacks into the conference.

“I knew we had problems with blacks [being accepted] at the time, and even in Sioux City, sometimes they had a hard time with housing. Often the dorms would take them or they’d stay in peoples’ homes. Going up to Sioux Falls, we had problems there with them staying in hotels. But that’s just the way it was and you lived with it.”

Though the NAIA didn’t allow black teams at first, Morningside’s insistence led to other colleges following suit, with the NAIA later crediting Morningside with breaking down the barrier.

“In NAIA that third year, we had 32 teams in our national tournament,” Buckingham says. “They finally let in one conference of blacks, then we finally had three. And they were really good teams.”

‘I’ve enjoyed my life’

Buckingham discovered early on the key to a happy life.

“I learned not to fret too much,” he says. “I used to be a worrier, but then I discovered one time that I’d gone a week and was trying to remember what I was worrying about the first part of the week. I couldn’t remember, so I figured ‘what the heck.’ Most of the times we’re fussing over things that really don’t make that much difference.”

That attitude took him far, through a host of different countries, and not only earned him respect from the players but international recognition as well. For a boy who grew up in Westfield, just 20 miles northwest of Sioux City, the road was long and winding.

As a Morningside college student, Buckingham and the Mustangs were back in the NAIB’s Championship title game for the second year in 1938. After playing in the game the first three years, Buckingham went on to spend the next 17 as the Mustang’s head coach. In 1948, he took over as Morningside’s athletic director and held that title until 1969. From 1965 to 1966, Buckingham also served as the NAIA’s president.

“I think I am the only person who played, coached and was also president,” says Buckingham of the NAIA.

During his time at Morningside, Buckingham also served as director of phys-ed and started their public relations department.

Olympic involvement

Buckingham spent 20 years involved with the Olympics, the first 12 on the board where he started a housing job, then stayed in housing up through 1984.

“We had the Pan American Games and Winter Games and Olympic games, and we had another group called the U.S. Sports Council, which is now under the Olympics,” he says. “The students had started the Council out of Italy. They have sports like the Olympics but it’s the younger kids and had age limit restrictions.”

Those games came to be known as “World University Games,” in which Buckingham served as president during the 1960s. His role as “Chief d’ mission” — or “chief of the mission” — took him to Sophia, Bulgaria, as well as Asia, South America, Europe, Canada and Mexico City.

Last year, Morningside alumni and their basketball players presented Buckingham with a plaque that honors his years of service. Missing from the event was Marian — Buckingham’s wife of 47 years — who died 3-1/2 years ago and whom he credits for making his life a success.

“We have three children, and she did most of the raising because I was always traveling,” he says.

He plans to donate the plaque back to Morningside where it can serve as inspiration for others. It also will represent a man who, according to Buckingham, “must have been doing something right because they kept me.”

I was fortunate to having lived next door to Al and Marian Buckingham during world war II he was stationed then at the jacksonville Naval Air station. Their oldest daughter was just an infant at that time. I was only 12 years old. The good ole days at Jax Beach Fla.