Price Hikes Lead to Rash of Metal Thefts

Thieves target copper, aluminum, and bronze—even if it’s bolted down

By Emma Schwartz

Posted March 27, 2008

In Columbus, Ohio, Reeb-Hosack Community Baptist Church has paid $15,000 to replace two stolen air conditioners. In Lake Worth, Fla., in January, $18,750 worth of bronze and brass pots disappeared from the graves of a local cemetery. And in the Central Valley of California, pilfered metal from irrigation equipment cost farmers millions of dollars last year alone.

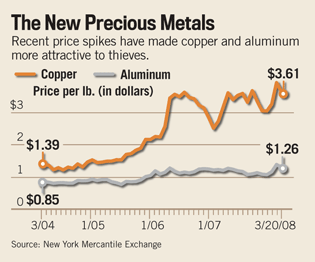

Across the country, metal theft is dramatically on the rise, and it is taking a heavy toll on businesses, homeowners, and law enforcement. The cause is the soaring price of, among other materials, copper, aluminum, and bronze. Copper, for instance, fetched just 75 cents a pound five years ago; now it is worth more than $3.60, largely because of increased demand from China and India. “Thieves are always looking for targets of opportunity,” says Bruce Savage, spokesman for the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, “and this is suddenly a new sort of opportunity.”

Across the country, metal theft is dramatically on the rise, and it is taking a heavy toll on businesses, homeowners, and law enforcement. The cause is the soaring price of, among other materials, copper, aluminum, and bronze. Copper, for instance, fetched just 75 cents a pound five years ago; now it is worth more than $3.60, largely because of increased demand from China and India. “Thieves are always looking for targets of opportunity,” says Bruce Savage, spokesman for the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, “and this is suddenly a new sort of opportunity.”

The opportunities seem to be everywhere. Catalytic converters—sources of palladium and platinum—have been pulled out of cars, gutters and aluminum siding are being ripped off occupied houses, and foreclosed homes are being stripped of copper pipes and wiring. In Fullerton, Calif., the Golden Hill Little League was forced to cancel practices and reschedule games when the theft of copper wire disabled its lights in February. “To put it in kids’ words,” says league president Kurt Blodgett, “it was just a big bummer.”

Utilities, not surprisingly, have been particularly vulnerable to metal thefts. A break-in last summer led to a power outage at a rural outpost of the Ohio Rural Electric Cooperatives. And thefts are now so common at unguarded substations that many utility representatives have simply stopped reporting them. “We just can’t seem to get control of it,” says spokesman Steve Oden.

Although stolen metal is worth a lot to the thieves, many of whom, police say, are drug addicts looking to support their habits, the costs are far higher for businesses and homeowners who must fix damaged property. Three men arrested in New Jersey last month for stealing copper bricks from cellphone towers estimate they netted $3,000 from each tower, police say. But the cellphone companies will have to pay between $2,000 and $5,000 for each tower to make repairs.

Cracking down. Some robberies have ended in tragedy. In Iowa, someone stealing copper pipes from a farmhouse last August accidentally cut the propane line, filling the house with gas, says Monona County Sheriff Jeffrey Pratt. When the 80-year-old owner tried to plug in a fan, the building exploded and killed him.

One reason for the growing number of metal thefts is that many states don’t require scrap metal dealers to keep good records about whom they purchase materials from. And even where laws do exist, police have been slow to enforce them.

That is beginning to change. Last year, 26 state legislatures and several cities toughened penalties for metal theft or increased reporting requirements for scrap dealers. Most simply require dealers to record identification information or a thumbprint of sellers so that stolen goods can be traced.

But some of the most successful efforts have come through old-fashioned police work. In Macon, Ga., police formed a committee of scrap dealers, home builders, utilities, railroads, and prosecutors in the fall of 2006. They developed an alert system for stolen metals and lobbied for a state law making theft above $500 a felony. The results look promising: There were 84 metal thefts in December 2006; in February of this year there were just 18.

Elsewhere, though, the problem remains as stubborn as ever. Phoenix has watched metal theft rise by more than 400 percent since 2003, causing damages of more than $7.2 million last year. New state reporting requirements have helped, police say, but a sting operation ending in January found that nine out of 25 scrap dealers were out of compliance. Police Chief Raymond Hayducka of South Brunswick, N.J., says there is a limit to what law enforcement can do. “If there’s a market for it,” he says, “people are going to try to obtain it.”

Copyright © 2009 U.S. News & World Report LP All rights reserved

More articles on Earl Thelander death

Leave a Reply