‘Sex-Crime Panic’ Revisits Ugly Sioux City History

By Jody Ewing

March 21, 2002

Iowa’s 1955 Criminal Sexual Psychopath law lumped homosexuals together with child molesters and murderers.

Iowa’s 1955 Criminal Sexual Psychopath law lumped homosexuals together with child molesters and murderers.

Sioux City, Iowa – what better place to live in 1954? Communities of unlocked houses, children playing in the parks, church bazaars and friendly neighbors. And somewhere beneath it all-corruption, payoffs, prostitution, murder.

It began one hot August night when 8-year-old Jimmy Bremmers disappeared. After the discovery of his body, Ernest Triplett – a 50-year-old music salesman with Flood Music – was arrested for the crime. While under arrest, Triplett received large quantities of LSD and amphetamine in attempts to coax him into a confession. No confession, no motive, no evidence. Convicted of the brutal murder anyway, Triplett was confined to the state mental hospital.

By April 1955, Iowa had established a new Criminal Sexual Psychopath law, lumping together homosexuals, child molesters and murderers.

After the July 1955 murder of another child, Donna Sue Davis, the Mount Pleasant Hospital established the Mental Health Institute for the Insane and Inebriates. Nineteen other men quickly were rounded up and presented for admission to Ward 15 East:

“Do you know what your name is?”

“Do you know where you are?”

“Do you know what the date is?”

“Do you hear voices?”

Despite the answers, diagnoses were the same: “Sociopathic personality disturbance. Sexual deviation (Homosexuality).”

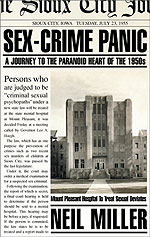

Thus begins Neil Miller’s chilling new book, “Sex-Crime Panic: A Journey to the Paranoid Heart of the 1950s.” It tells the harrowing story of 20 Siouxland homosexuals who were sentenced to mental institutions after the murders of two Sioux City children, though they had nothing to do with the crimes.

Miller, author of several books on the history of gays and lesbians, will do readings and signings on Wednesday, March 27, at Morningside College and Book People.

“It’s going to be sort of a half-talk, half-reading, where I lay out the whole story and talk about its relevance to today,” said Miller in a telephone interview. “It’s a lot of Sioux City history of the 1950s, and of the roundup of those men.”

A journalism and nonfiction instructor at Tufts University in Medford, Mass., Miller conducted interviews with formerly incarcerated men, law enforcement officials, lawyers, mental hospital staff and relatives of the murder victims.

Gail Dooley, associate professor of music at Morningside who coordinated Miller’s visit, says the book is thoroughly researched and does not portray the college or city in a negative way, as some had feared.

“That kind of thing was not necessarily unique to Sioux City, it just so happened it was Sioux City,” Dooley says.

It was a volatile time for Sioux City, says Vickie Hassenger, owner of Book People in Marketplace Mall.

“There were all kinds of things going on, and to calm people, that’s what the police felt they had to do,” Hassenger says. “At that point I didn’t know what ‘gay’ was, and we didn’t talk about sexual psychopaths.”

The Details

Who: Neil Miller, author of “Sex-Crime Panic”

What: Lecture, book signing and reading

Where/When: Morningside College, UPS Auditorium, Wed., March 27, 10 a.m.;

Book People, Marketplace Shopping Center, Wed., March 27, 4:30 – 6 p.m.

For More Info: Call Morningside at 712-274-5208 or Book People at 712-258-1471.

Yet the outcome and treatment of those confined to Ward 15 devastated many Sioux City families. Miller writes in his book: The walls were smeared with excrement. The smell was ghastly – a combination of urine and feces and disinfectant. It was the “untidy ward,” where psychotic men who had regressed to a near infantile state were housed.

“It was awful. People were treated like animals,” Hassenger says. “It’s like they were scapegoats because they couldn’t solve the crime.”

Dooley says Morningside has since taken an active role in educating students and the public on gay and lesbian issues.

“We have had what we call LGBT – lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgender – awareness days for over 20 years,” says Dooley, who also serves as faculty advisor for Morningside’s Gay Straight Alliance. “We usually have outside speakers come in for awareness days and we often have panels, discussing things ranging from what it is like to be an openly gay or lesbian person in Sioux City, to panels discussing the implications of homosexuality and religion in our society.”

Morningside’s administrative position, Dooley says, is that they are an institution of higher learning, and if one is going to talk about any uncomfortable or controversial issue, it should be at an institution of higher education. The college also welcomes speakers with opposing views.

‘Fascinating Story’

Miller says he ran across the story while doing research on his gay history book “Out of the Past,” and that it stood out in his mind from the start.

“I was just kind of fascinated by the story, and whatever happened to them,” Miller says of the 20 men. “No one had ever heard of this thing. What was it all about, what happened to these people, and what was the real story here?”

Miller points out that the sexual psychopath law of 1955 (which wasn’t repealed until 1977) should be considered in light of more current legislation. For instance, all 50 states have adopted some version of Megan’s Law, which requires convicted sex offenders to register with local police departments, making their names and addresses available to the public.

With gay characters now on television and the subject more in the forefront, things are changing, he says, though stereotypes continue to exist.

“As long as gay people across the board are reluctant to come out of the closet, then those stereotypes continue to flourish,” he says. “I don’t think something like that would happen today, but I do think there are lessons. There are lessons about civil liberties and the ability of the majority to sort of persecute unpopular groups of people.”

This article first appeared in the Weekender on March 21, 2002.

Leave a Reply