From college lecturer to Callgirl and back

A talk with author Jeannette Angell

By Jody Ewing

October 7, 2004

People want to talk about it, and they ask the same questions over and over. How did you get started? What’s it really like? What kind of girls work for the service, and what kind of people use it? They can’t get enough information on what seems to them a semi-forbidden world.

The job is working as a callgirl for an escort service — a world caricatured by pornography and speculated about by almost everyone.

It’s also a world where Jeannette Angell — with a doctorate in social anthropology — spent three years working as a $200-an-hour Boston callgirl by night while working as a university lecturer by day.

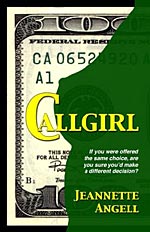

The French-born Angell, who earned her master of divinity degree at Yale and her doctorate from Boston University, has written a studious, yet insightful account of those years in her memoir “Callgirl,” a behind-the-scenes look at one of America’s most mysterious and misunderstood professions.

Angell’s decision to work as a callgirl had more to do with rent than research. She’d just begun a new semester teaching a series of college lectures when a live-in boyfriend vanished, having first wiped out her bank account along with her prepaid salary. Boston’s rent didn’t come cheap and was also due. She needed lots of money, and she needed it fast.

The mid-level escort service, run by a woman whom Angell calls “Peach,” stood out among the ads in that it required a minimum of some college education. Angell imagined the worst, but found most clients an invisible, unremarkable group of men: lawyers, stockbrokers, those about to be married and even university faculty. There were others, however, who insisted on degradation. “You’re just a whore,” a man named ‘Barry’ tells her. “You do what I say.”

Angell kept her second job secret from those with whom she worked, and after confiding in a few close friends discovered the damage stereotyping breeds. She’d eventually give up her night job, but not before creating a new university course, “The History and Sociology of Prostitution,” which explores both the history of prostitution and how mainstream society interacts with it.

In an e-mail interview from her Boston home — where Angell lives with her husband and stepchildren — she talked about “Callgirl” and the most violent elements in society.

Imagine that a person who doesn’t know anything about you or your novels is about to pick up a copy of “Callgirl.” If you could tell them just one thing before they started reading it, what would you say?

One of my teachers in grammar school, a nun, used to say, “La vie, c’est bien compliqué.” I’m not sure what that meant to me at the time, but it’s become the guiding principle of my life, my writing, my interactions with others. Life is very complicated indeed, and that’s what makes it both difficult and interesting. Stereotypes, racism, xenophobia — most negativity in the world comes out of the natural human desire to oversimplify. Life isn’t simple, and that’s what “Callgirl,” “The Illusionist”…*all* my books are about. That life is more complicated than it appears, and that people really do their best, most of the time, to work through those complications.

What does “Callgirl” attempt to do, and for what kind of reader was it written?

Callgirl is a window, an opportunity for readers to see into a world they would otherwise never know and to experience it from the inside. That’s really all. I think that once one has read the book, it will be a lot less easy to make hooker jokes, for example. Most of our hatred comes from ignorance. Once one knows people from the excluded group (be they people of another race, religion, political party, or profession) it’s a lot harder to hate them. So “Callgirl” was written for all the people who dismiss sex workers as criminals, nymphomaniacs, people of loose morals. Just to have them read the book is a step in the right direction.

What provokes you to begin a book: an image, a character, a setting, a feeling?

Almost always a character, almost always that character or characters in a situation that puzzles me. “The Illusionist” began when I read a newspaper account of John Demjanjuk’s arrest for crimes against humanity; his son was quoted as hotly protesting his father’s innocence. Well, I remember thinking, of *course* he’d have to say that, how could anyone accept that a loving parent might also have been a torturer and murderer? “Wings” and “Flight” are both about a family’s choices during two world wars — again, I found myself wondering about how women were responding to and dealing with their families’ participation in various facets of the wars. I start with people and then examine how they think and feel and behave under pressure.

What types of characters interest you most? What sorts of stories?

The ones that we can’t figure out. The ones that haunt us, that we can’t get out of our minds. My upcoming novel, “In Dark Woods,” came out of another newspaper account. I read years ago of a woman whose child was murdered and who became subsequently obsessed with the killer throughout his trial, to the obvious delight of the media. What was going on in her head and her heart? Perhaps that’s why I’m fascinated by history, because it’s filled with people behaving in ways that I find inexplicable, and I spend far too much time wondering how they came to act as they did!

You were born and grew up in France at age 21 — can you describe any differences in culture as far as how they, vs. the U.S., view prostitution?

There’s a whole different take on sexuality in general, so naturally there’s trickle-down to the issue of prostitution. The United States has never shed its Puritan past. Just compare this country’s reaction to President Clinton’s well-publicized extra-marital affair with France’s reaction to that of President Mitterand – his wife and his mistress both attended his funeral. I think that sexuality in general and prostitution in particular are more accepted components of life than they are in the States. In the US, everybody knows it happens but nobody wants to talk about it, as though somehow the very articulation might make it real. In France, it’s discussed. French people don’t make a distinction between the intellect and that which is sensual; it’s all part of the human condition.

Your friendship with Sophie addresses “the addict’s gift of the silver tongue” — of making those who care about them believe they can help or cure the addiction. When does one say “enough,” and how does one know they are doing the right thing?

Well, my description in the book shows that I had no idea how to answer that question, back then. Sophie haunts me to this day. I’ve learned a lot since then about dealing with addicts, and know that one ought to say “enough” from the beginning. Help is not doing what that person wants you to do, or even what you want to do — help is getting them into rehab. Period. I didn’t know that at the time. In many ways, despite the sophisticated veneer I liked to assume, I was very naive.

In Chapter 11, while talking to a student, you say that parents want their children to be independent thinkers, yet don’t realize their children may make choices that are different from their own. In this Baby Boom parent era, when it comes to social issues (racism, sexism, etc.), is it possible for an educated child to really get through to an uneducated parent whose beliefs were firmly planted by their own uneducated parents? If so, how?

Given the issues in family dynamics, I don’t know if that’s possible. My father-in-law is racist. He’s also in his eighties and very ill. Am I going to change his mind? Doubtful. I’d rather invest my time trying to touch people who still have time and reason for change. We’re all to some extent the products of our environments and upbringing. I’ve not accepted much that my parents believed to be true, but I also realize that they gave me the tools with which to think critically, and that made all the difference. Perhaps we can teach everyone — parent, child, friend, acquaintance — best by example.

In today’s society, the “perfect woman and perfect sex” are as close as one’s computer and an Internet connection. “Callgirl” addresses this ‘perfect woman’ myth; she’s there to please the man and has no needs, no desires, no demands of her own. Since neither prostitution nor Internet-based sex will ever disappear, how does today’s intellectual woman compete with that “perfect woman” myth?

I think that the fantasies will always be part of being human, because we’re none of us exactly what others want us to be — and nor are they perfectly what we want, either. Women do the same thing, you know — look at the success of romance novels: those are women’s Penthouses, Playboys, Hustlers. Face it, we all have fantasies of what our perfect partner should be like. Ideally, we learn that those are in fact fantasies and that real life is — you knew this was coming back — more complicated. It’s when that line between fantasy and reality becomes blurred that there are problems. I think that the divorce rate has to do with that line being blurred, that people are disappointed when their partner isn’t a fantasy but a real person, and so they seek out someone whose very newness holds out the possibility of becoming the fantasy… until that person, too, becomes real, and the cycle repeats.

Your reference to Emma Goldman’s phrase — “The most violent element in society is ignorance” — is more critical today than ever, yet people continually base opinions on ads they see on TV or ethnocentric ideals. When it comes to ignorance, what is its biggest danger?

Its biggest danger, I believe, is that ignorance is blinding. We fall in love with what we believe, and become resistant to change, to seeing a different viewpoint, to the point of not even acknowledging that there may even be another valid viewpoint. When that happens, we’re blind — blind to ourselves, to others, to what matters. And if one of the goals of life is connection, then this has to be its opposite, because it disconnects us from the rest of humanity.

You recently appeared on Oprah. Can you tell me about that experience, and what you learned from it?

“Still naive after all these years” would sum it up nicely, I fear. I believed what I was told by the producers, and I should not have done. They indicated that I would be promoting my book, and instead I was presented in a sensationalist, tabloid format. Oprah herself surprised me by not reading the book and by the personal nature of her attacks (after the show, in the green room, she made a point of embracing all of the other participants — then looked straight at me and walked away). It’s unfortunate that the show chose to go down the sensationalist route, and ironic that I was essentially being accused of being immoral; I found what they did to be far more immoral.

If prostitution were to be legalized, how do you perceive things would change?

Women would be safer. There’s no question about that in my mind. Right now, sex workers are extremely vulnerable because they have few choices in finding safe employment and no recourse when something goes wrong. Sex workers would participate in their communities through taxation, as do other professions. Would the stigma disappear? That’s another issue, though it has been my experience that the people who voice their disgust with prostitution the most loudly are the ones who are the most titillated by it — so that is, indeed, a different question. I strongly believe that it should be legalized and regulated, which in essence has nothing to do with the morality issues: there are plenty of other things that are legal but, to my mind at least, not moral at all.

How has your own life changed since the book’s publication?

It’s interesting — it’s the first of my books to have changed anything in my personal life. Usually I write a novel, it gets published, people read it… life goes on. In one sense, it’s a job. But this time was different. It’s understandable, of course — it’s the first book I’ve written that is about me, per se, rather than about how I write or whether I can tell a good story. Many of the reactions I’ve received have been about me, personally; and I’m learning to deal with that.

Why do you write?

If I may borrow a phrase from Toni Morrison — “I’m just trying to look at something without blinking.” That really sums up my writing — I look at things and try and figure out why they are the way they are, and the way that I do that is by writing about it. I’ve always thought better with a pen (or PowerBook!) in hand.

Anything else?

Best questions of any interview I’ve done — and I’ve done a great many! Thank you for allowing me to think.

For more info on Callgirl and the author’s other novels visit: jeannetteangell.com.

Excerpts of this article first appeared in the Weekender on October 7, 2004.

Copyright © Jody Ewing, 2010

Great interview, I was rereading CallGirl and looking for more information on Jeanette, not much out there, Jeanetteangell.com is now a fitness site by a young woman with the same name. And I have not been able to find In Dark Woods, if it was ever published. Shame I was excited at the possibility.

I loved the Quote about, ““I’m just trying to look at something without blinking.” I think thats just what CallGirl does, and what draws me to Jeanette as an Author. It takes real courage to write like that, certainly real courage to write CallGirl; and stand behind it since.

You did real justice to an exceptional woman. Thankyou, Blessings, BB.

The Universe has a sense of Irony, just minutes after I posted my comment: I discovered, “In Dark Woods” was published by Jeannette de Beauvoir, which seems to be her pen name now, and http://www.jeannettedebeauvoir.com is her current site. I’m quite sure of this, her face is unmistakable. BB.

I know her personally- and regardless what people say, I can confirm everything she said is 100% factual.