‘Quacks’ features notorious Iowa con man

An Interview with BCU professor and author Eric Juhnke

By Jody Ewing

December 18, 2002

One man promoted goat gland transplants as a remedy for lost virility or infertility. Another blamed aluminum cooking utensils for causing cancer. The Food and Drug Administration targeted a third as “public enemy number one” for his worthless cures.

With backgrounds varying from low-brow performance carnivals to vaudeville and running for governor, John Brinkley, Norman Baker and Harry Hoxsey were the ultimate charismatic con men of the 20th Century. While they scorned the medical establishment, each amassed fortunes while preying on the ignorant. Baker — a flamboyant radio broadcaster from Muscatine, Iowa — once publicly administered his “special powder” on a farmer’s brain whose partial skull had been removed.

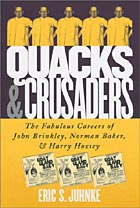

In his new book “Quacks and Crusaders: The Fabulous Careers of John Brinkley, Norman Baker, and Harry Hoxsey,” Briar Cliff University assistant history professor Dr. Eric Juhnke examines the career of each man and the connections between fraudulent medicine and populist rhetoric.

Weekender writer Jody Ewing talked with Juhnke about quacks, cons and the roles they play today.

Eric Juhnke |

You say in the book’s acknowledgements that John Brinkley brought your grandparents together. You researched quackery as one of your father’s undergraduate students, and your mother is a college health administrator and nurse. Given these elements, was there one thing in particular that prompted you to write this book, or had you always known that someday you would write it?

It was really a case of serendipity. I discovered Norman Baker while writing my senior thesis on an uprising known as the Cedar County Iowa Cow War of 1931. Some farmers in eastern Iowa rebelled against state veterinarians’ efforts to enforce mandatory bovine tuberculosis testing. In my efforts to understand the farmers’ motives, I learned that Baker, who had lambasted organized medicine over the airwaves for years in defense of his cancer hospital, convinced some farmers that the tuberculosis test was part of grand conspiracy for meat packers to obtain cheap beef.

The more I learned about Baker’s career as a cancer quack the more fascinated I became. I had known about Brinkley before and Hoxsey’s name kept popping up in my research, so I added them to the mix.

What does “Quacks and Crusaders” attempt to do and for what kind of reader was it written?

This book tells the stories of three of the most successful medical charlatans of the 20th Century. In that sense, it is a multi-biography aimed for a general audience. However, the book is as much analytical as it is narrative. My thesis counters traditional scholarship on the history of medicine, which suggests that quacks were always villains, their patients ignorant suckers and medical doctors, heroes. The reality, I argue, was much more complex. Overall, my hope is that readers will find the book both entertaining and useful in explaining the nature and influence of quackery in the past and the present.

Although the incidents in the book took place from the 1920s through the 50s, the increases in the NCCAM (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine) budget show that there is a growing acceptance of alternative medicine. How do you explain this?

The American public has long sought alternative methods of treatment for chronic and life threatening illnesses. What the NCCAM’s budget reflects is that organized medicine (the AMA, FDA, MD’s, etc.) has softened its position against non-allopathic treatments due to overwhelming public pressure, scientific studies supporting alternative methods, and the popularity of less invasive, holistic medicine. Nevertheless, organized medicine has remained cautious, and for good reason, since alternative medicine has provided fertile ground for various forms of quackery in the past.

In what types of forms (or disguises) does quackery appear in the medical forum as well as other organized fields?

Quacks include those who, out of conscious deceit rather than ignorance, make fraudulent claims about the effectiveness of their cures, solutions, or abilities. Consequently, quackery can be found in almost every profession. Their disguises vary as much as their fields. Whatever their angle, all successful quacks are able to manipulate the fears and insecurities of their victims.

Of the three men in ‘Quacks,’ who do you feel was most dangerous and why?

I believe that Harry Hoxsey represented the gravest threat to the American public, because he attracted the largest following and “practiced” medicine the longest. Although we can safely assume that a large percentage of Hoxsey’s patients never had cancer as his doctors professed, certainly there were genuine cancer sufferers among the hundreds of thousands who received the “Hoxsey cure” over a 40-year span who would have lived longer had they availed themselves to conventional care.

Do you have plans for a future book?

Currently, teaching and parenting responsibilities afford little time to complete another book. However, I hope to continue my research on this subject and eventually write a history of cancer quackery in the United States.

Quacks and Crusaders is available at local book stores and through University Press of Kansas at www.kansaspress.ku.edu or through amazon.com.

you should be ashamed. you have not done adequate investigation. people treated by these men were sent home to die by the conventional care whose lies you tout.