It’s hard watching dogs grow old. Watching as their eyesight slowly starts to fade. Knowing their hearing isn’t quite so sharp. Seeing them struggle a little more than usual as they strain to get up after a long, peaceful nap.

It’s really hard. Especially when you can’t ever remember when they weren’t around.

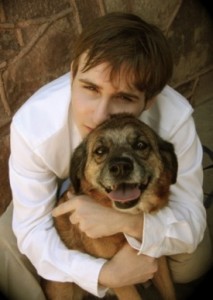

My dog Cocoa — the oldest of our three — will be 14 years old in June. Monday I took him to the vet for a medical procedure on his “back end,” and it wasn’t a pleasant experience for either of us — least of all him.

I discovered Cocoa’s “problem” in the hours before the sun came up Saturday. Housebroken almost from the day he was born, he was crossing through the front foyer on his way into my office when suddenly he froze midway and began urinating on the hardwood floor. I’d just sat down at my desk and quickly went back to him, but he only stared up at me with eyes that said he didn’t quite understand what was happening.

“Come on, boy. It’s okay. Let’s go outside,” I said, but his eyes never left mine and deep inside I knew everything was not okay; in less than two weeks, it wasn’t the first — nor the second — time he’d had an indoor accident after 13 and one-half years of never having gone inside the house before. And even on recent days when I’d sat in the kitchen sipping coffee, he’d lain on the floor three feet away but hadn’t rested his muzzle between his paws like he normally did. Instead, he lay there with his head up and alert, not moving a muscle as he fixed his eyes directly on my face and stared minute after motionless minute.

So just after 2 a.m. on Saturday, once I’d wiped up his latest accident and let him out and then back in, we went back to my office and I sat down beside him on the big folded comforter I keep beside my desk for the dogs when I’m working. He put his head in my lap as I stroked his back, and I unfastened his blue collar to better scratch his neck.

“You going to be okay today, Cocoa Bug?” I asked. “Rhett’s going to stay with you while we’re gone.”

Dennis and I were scheduled to leave at 5:30 a.m. for Des Moines, where I’d attend a Democratic State Central Committee meeting before we headed over to Governor Culver’s home for his annual holiday party. My son Rhett — who’d planned to leave Friday to spend the week with his father — had stayed over for the weekend so he’d be there to care for Cocoa and the other two, Bear and Hagan, while we were gone.

I looked down at the moose and trees and leaves populating the fall-colored comforter and wished for warmer days with no ice and snow where we could take the dogs out to play and for long walks in sunshine.

At 3 a.m., Cocoa and I stood up and parts of his still shedding winter coat floated off my pajamas as we made our way to the kitchen for a snack. Once he’d finished his Milk Bone and waited while I puttered around tidying up the kitchen, I put my hands on either side of him and moved them back and downward towards his tail, feeling for anything unusual like I often saw the vet do during the dogs’ check-ups.

That’s when I felt it. Something hard and dry. On both sides of his backside just below his tail. How had I missed it earlier while on the floor petting him?

“Cocoa Bug, what do you have there? Some dried poopie on your butt?” I asked, and then, turning him around so his tail faced toward the light, I bent down and tried to lift his tail to have a look. He slipped from my hands and ran into the living room, and I coaxed him back only after bribing with another treat. This time I’d be ready. He tried to get away again but I held his chest with my left arm and carefully lifted his tail with my right as I bent around for a quick peek. The instant I gasped he bolted.

I stood in the middle of the kitchen, dazed, still bent over, wondering what on earth I’d just seen and asking myself what possibly could have happened. Had he been attacked? No. He couldn’t have been. With the freezing temperatures, he’d seldom been outside except to relieve himself. And it had been months since anyone left a gate open and they’d gotten out.

The dogs didn’t fight, and hadn’t since years before when Hagan first came to live with us in ’06 and Cocoa showed him, in short order, that there simply wasn’t room in this big house for two alpha males. And deep down inside, I think I already knew the dried and fresh blood I’d just seen — along with something else I knew didn’t belong on the outside — had not been caused by another dog nor anyone else.

By the time I got upstairs to awaken Dennis and tell him what I’d discovered, Cocoa was already in the bedroom, hunkered down safely between Bear and Hagan and glaring at me as if I’d somehow betrayed him. It was just before 4 a.m. — the time I’d originally planned to get up and shower. I’d never even gone to bed.

We did not go to Des Moines, and Dr. Sulsberger answered the veterinary clinic’s phone later when I called. He said from what I described, it sounded like an abscessed anal gland.

His assessment was correct — despite my insistence that Cocoa hadn’t shown any symptoms and hadn’t even been “scooting” across the floor (“Aren’t they supposed to scoot if there’s a problem with their anal glands? Now Bear, he’s a scooter!” I’d told him) — and he scheduled Cocoa’s “procedure” for Monday morning.

Sunday night when Cocoa started up the steps for bed and turned around to wait for me, I stood at the bottom and told him I’d be up soon and it was okay to go ahead without me. Still, he waited. “Go ahead, boy,” I said. “It’s all right. You can keep Dad and Bear and Hagan company.” His tail swished back and forth just a little, and then he turned and started upward, his back legs stretching out stiff and his body moving awkwardly like a toddler with a soiled diaper as he climbed the stairs one by one.

Not so very long ago, he’d scaled the staircase quickly and silently — graceful like a gazelle — leaping upward two and three steps at a time. And he’d never had trouble jumping to the bed where he slept most nights. In one seamless movement, he’d go from floor to bed and then drop to his stomach before slinking his way up the bedspread until his head fit comfortably on my shoulder or was nestled in the crook of my arm. Lately, though, he’d begun to fall. He’d make the jump but not quite make it all the way, and he’d cling to the bed with his front paws for a brief moment before toppling over backwards.

I’d get out of bed and wrap my arms around his front and back side to lift him to the bed, and though he’d assert an objectionable low growl — after all, who was I to imply he might need any help? — once I set him on the bed he’d sigh with content as he plopped down in that very spot. Later in the night, I’d feel him jump from the bed and hear him drinking from the water bowl before settling in on one of the two large foam-filled camping mattresses covered in quilts that easily accommodated the three of them.

Bear, fast approaching his 11th birthday in April, had given up on our bed two years earlier. He used to sleep next to Dennis with his head on my pillow until I came to bed, and on occasion, if there was room and I found him sleeping soundly, I’d inch into bed and sleep along the very edge until Bear woke up some time later and decided he’d join Hagan. The queen-size bed wasn’t big enough for two adults and Cocoa and a Chocolate Labrador and Chesapeake Retriever.

The sound of Bear’s feet on the steps changed within those two years, too. It’s now a clumpity clump, clumpity clump, clumpity clump, all the way up. His hearing is all but gone but he still has a keen sense of time and knows exactly when the neighborhood kids will be walking home from school so he can go out to greet them or watch as they pass by and he’s already waiting expectantly when Dennis pulls into the driveway after work.

Bear is also the healer of the three and the first to alert me if Hagan’s ears are acting up again. Had I paid better attention I would have known a few days earlier that his nose butting up next to Cocoa’s tail in the morning as we headed from the bedroom to go downstairs was something more than him trying to hurry Cocoa along.

And so it was that on Monday morning when I reached for Cocoa’s leash, none of them reacted. On any other given day they’d be dancing in circles knowing they were going on a fun walk or ride. But they all knew. There was no running around the coffee table knocking off books and papers. No crashing and bouncing into one another in anticipation. No charging toward the leash in my hands with a Me First! attitude. Only blank stares.

They’d seen me fasten Cocoa’s collar but not so much as reach for theirs. They knew Cocoa hadn’t been himself; early Saturday morning Hagan had sniffed at the spot in the front entry and flashed his eyes up at me as if to say “Did you know about this!?” And, how could we be going anywhere when I hadn’t yet fed them? I’d told Rhett to wait to feed the others until after Cocoa and I were gone; I wasn’t sure if general anesthesia would be used and didn’t want to take any chances.

Cocoa didn’t protest my hooking his leash to his collar, but he looked back forlornly at Bear and Hagan, who’d quietly stepped a few paces backward. I fully understood their silent language. Sorry, Cocoa, we’re not coming with you. You’re on your own, old boy.

Dogs, I am certain, know more than how to say hello. They know how to say goodbye.

On the 18-mile ride over to Mapleton, Cocoa would not sit down in the passenger seat. He looked from the outside snow-covered fields back to me, uncertain and disheartened, and every two or three minutes approached the driver’s seat to lick my cheek. But as much as I tried to soothe him and cheerfully reassure him everything was going to be okay, he knew things were never okay any time Dennis or I left the house with only one of them. And without breakfast.

Misfortune had fallen. And in a stroke of purely bad luck, he knew it had befallen him.

General anesthesia wasn’t used, and with his head planted firmly on my shoulder and my arms snugly wrapped around his neck and shoulders, Cocoa grudgingly endured what Dr. Sulsberger and his technician were doing behind him. When they’d finished, Dr. Sulsberger turned Cocoa’s back side around until it was between us and then opened a tube of ointment capped with an elongated, slender tip.

“Now watch what I’m doing here,” he said. “You’ll have to do this twice a day for the next two weeks. You see that little hole ….”

Me? Did he say me? And twice a day for two weeks?

But as he further explained how it needed done just right and I indeed paid meticulous attention, I didn’t let on I already knew Cocoa would never let me get anywhere close to his behind once he made it off that stainless steel table and got back home on his own turf, let alone get close while armed with intent.

When it was time to leave, Cocoa jumped up straight into the truck’s passenger seat without any help and sat there grinning like a cheshire cat. All the way through the hills and down the winding road, he never stopping grinning. I’d never seen so many of his teeth all at once. He knew he was going home.

Bear and Hagan greeted us as if we’d been gone a week, and the three of them ran around the table to celebrate Cocoa’s homecoming. By the time I went up to bed that night, he was already there sleeping soundly on the bed.

Tuesday was the day; the dastardly deed needed done. Dennis closed the door between the kitchen and living room so Cocoa couldn’t escape while I warmed a washcloth. “You’ll have to hold his head, and don’t let him see what I’m doing,” I said. When I put the washcloth against his bottom, Cocoa promptly sat down on both the washcloth and my hand but it didn’t affect my ability to get at least that job done. Then, the pivotal moment arrived.

“You better do it fast and get it right the first time because you probably won’t get a second chance,” Dennis said as I uncapped the ointment and he called for Cocoa to come back to him. He took Cocoa’s head and held tight while I straddled Cocoa’s back and lifted his tail.

I couldn’t find the little hole. Cocoa began to thrash about and wrested his way out from between both of us. We tried a second time. “I see it!” I said, but the instant my arm brushed against Cocoa’s left back leg he launched into another struggle and wrenched his way out from between us again. Dennis sighed loudly while Cocoa stood across the room, his tail swishing back and forth again the dishwasher’s door as he grinned.

Finally, I approached him on my own. After all, how fair could it be — two against one. “It’s okay,” I said, and I kept repeating the words as he came to me and I tucked his head loosely between my legs. I don’t know if he remembered how many times I’d spoken those words while sitting that night on the moose comforter or during the ride over to Mapleton, but suddenly he stopped trying to run.

I lifted his tail. He stood perfectly still. I crouched over and got down to business. He didn’t even flinch.

Only when I rose and announced “All done! Good boy!” did he finally move. His entire body wagged as he pranced around the room in delight. And that grin and those teeth! One would have thought I held in my hands not a tube of ointment but three collars and three long leashes.

Dennis opened the kitchen door and Bear and Hagan rushed in to see what all the excitement was about and find out what they’d missed. Cocoa sprang forward to greet them and then with great joy darted over to stand directly beneath the counter where we kept the dog treats. The others quickly joined him and once I’d washed and dried my hands I forged through three swinging tails to deliver a well deserved reward.

On any other given day they’d have sat before I said sit or offered up a paw before I could say shake, but today they somehow knew and I asked them to do neither.

“I think I’ll do just fine on my own next time,” I told Dennis as I put the tube of ointment back into its box. Yes. I was confident. I — like these aging but happy three brown dogs — hadn’t been too old to learn a new trick.

We headed from the kitchen to the living room as a chorus of lively feet pattered close behind. They knew, indeed; everything was going to be okay.